CHRD releases “Repression & Resilience: Annual Report on Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2017)”

February 26, 2018 Comments Off on CHRD releases “Repression & Resilience: Annual Report on Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2017)”

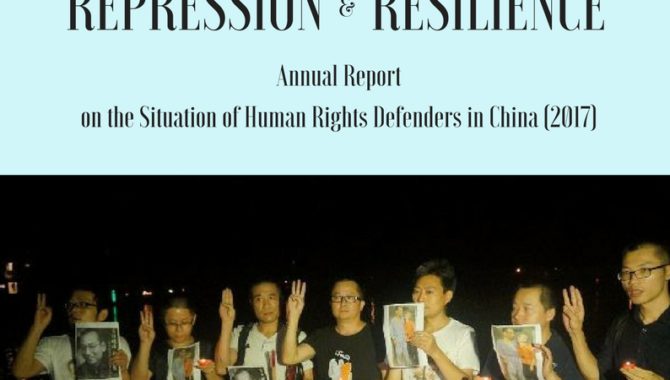

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders—February 26, 2018) – Chinese human rights defenders demonstrated remarkable resilience in promoting and protecting human rights in the face of government repression, says CHRD in its annual report released today. Repression & Resilience documents the situation of human rights defenders in China in 2017. As Chinese President Xi Jinping consolidated power and promoted his totalitarian vision, human rights activists mobilized, disseminated information online, gathered in protest, and formed alliances to defend human rights. Many faced detention, imprisonment, disappearance, torture, harassment, or administrative punishment for speaking out against government suppression.

In 2017, the Chinese government took an aggressive approach to undermining international human rights principles while it carried on severely violating human rights inside the country. The government actively pushed an alternative concept of “human rights with Chinese characteristics,” which prioritizes “development” over human rights, despite the failure of such a model at home. Abuses related to economic, social, and cultural rights, as well as to political and civil rights, remain widespread in China.

In 2017, the Chinese government took an aggressive approach to undermining international human rights principles while it carried on severely violating human rights inside the country. The government actively pushed an alternative concept of “human rights with Chinese characteristics,” which prioritizes “development” over human rights, despite the failure of such a model at home. Abuses related to economic, social, and cultural rights, as well as to political and civil rights, remain widespread in China.

When human rights defenders refused to back down and challenged repressive government policies, authorities subjected them to enforced disappearance, criminal prosecution, torture—including deprivation of proper medical treatment—and other types of mistreatment. The government’s ill-treatment of HRDs in custody may have directly contributed to the deaths of two prominent prisoners of conscience in 2017, including Nobel Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波).

Many Chinese human rights defenders revealed in 2017 that they had been tortured by police during secret detention under “residential surveillance at a designated location.” The government continued its persecution of human rights lawyers and obstructed their efforts to conduct their professional activities independent of government interference. Such lawyers soldiered on even as they remained at high risk of losing their licenses and being harassed, physical assaulted, detained, and criminally prosecuted. Authorities continued to harass and threaten reprisals against activists and lawyers seeking to engage with UN rights bodies.

The Chinese government tightened controls in three particular areas of civil liberties important to ensuring a safe environment in which HRDs can conduct their work—the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and free association. These rights are key to the effective monitoring of and advocacy for a wide range of human rights.

In the area of freedom of expression, Chinese authorities promoted “cyberspace sovereignty” and further tightened restrictions on free speech and sharing information online. Highly sophisticated cyber controls were ramped up in 2017, making it even riskier than before for HRDs to speak out about rights abuses and conduct advocacy work. Many HRDs in 2017 faced detention or stood trial for online speech, particularly expression over issues that the government considers “politically sensitive,” including expression mourning Liu Xiaobo’s death or views about the 19th Party Congress and Xi Jinping’s consolidation of his power.

Despite restrictive regulations on the right to peacefully assemble and the risk of persecution, large-scale protests continued to break out spontaneously—including protests against pollution, land grabs, forced evictions, and unfair wages. Activists gathered publicly to express their views, often assembling outside courthouses to support detained HRDs whose trials were held behind closed doors, or outside government buildings to demand official accountability for abuses. Throughout 2017, authorities put HRDs on trial for organizing or participating in peaceful protests.

Civil society organizations in China, including NGOs engaged in human rights advocacy, struggled for survival in 2017. Some groups persevered in the face of contracted space to operate amid ongoing suppression. Some groups shut down permanently, while others operated only in heavily-controlled cyberspace. Victims and activists continued to undertake collective actions in 2017, mostly in informal groups or loose alliances, in response to human rights violations. The year ended with some human rights NGO leaders languishing in custody on “endangering state security” charges for documenting human rights abuses.

CHRD urges the Chinese government to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms and end its repression of civil society, including HRDs. The government must: Release all detained and imprisoned HRDs and activists; investigate allegations of torture and ensure perpetrators are held criminally responsible; ensure that detainees and prisoners are promptly given access to proper medical treatment; repeal Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law and end the practice of forcibly disappearing HRDs and activists; guarantee that lawyers’ professional rights are respected; and repeal stipulations in national legislation which abridge the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association.

Contacts

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Researcher (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD