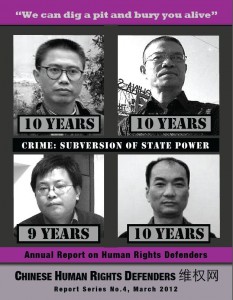

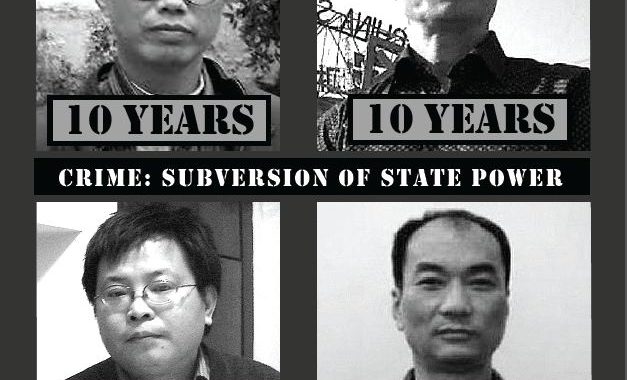

“We can dig a pit and bury you alive” Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China, 2011

Comments Off on “We can dig a pit and bury you alive” Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China, 2011

“We can dig a pit and bury you alive”[1]

Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China, 2011

Please click here to read the full report.

Introduction

The state of human rights in China continued to deteriorate in the year 2011. As documented in this annual report from CHRD, it has been a year of harsh crackdowns for human rights defenders (HRDs), characterized by lengthy prison sentences, extensive use of extralegal detention, and enforced disappearance and torture.

Against the backdrop of the wave of protests that swept across North Africa and the Middle East and brought down entrenched dictatorships, anonymous online calls in China for “Jasmine rallies” clearly unnerved the government. Large numbers of security personnel were deployed in the areas where protests were expected to take place; an unknown number of people (estimated in the thousands) who had spoken out on the subject or posted related information online, or who participated in the rallies, were seized and taken away for interrogation. Dozens of human rights activists, lawyers, and outspoken intellectuals were disappeared and tortured, and several veteran democracy advocates were sentenced to long prison terms.

This “Jasmine Crackdown,” felt most keenly by HRDs, marked yet another low point in China’s human rights, making 2011 the most repressive year since the rights defense (weiquan) movement began in the early 2000s. Among the rights defenders surveyed for this report, over half said that in comparison to the previous year freedoms of expression and assembly—essential prerequisites for the defense of human rights—had deteriorated in 2011. The crackdown impacted not only the individual activists, but also menacingly conveyed a warning to the ordinary Chinese citizens: anyone who challenges the government will be punished.

One of the most alarming developments in 2011 was the extensive use of enforced disappearance against HRDs. Although thousands of citizens are routinely held in illegal “black jails”[2] for complaining about government misconduct, the use of enforced disappearance, which occurred only rarely before the Jasmine Crackdown, was stepped up: at least two dozen high-profile activists across the country were disappeared and held for weeks or months at a time. In August, in an initiative designed to legalize enforced disappearance, the government announced draft amendments to the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) that would allow for detainees suspected of offenses “endangering state security” to be held incommunicado for six months, without any notification being provided to their families. It is expected that this legislation will be rubber-stamped by the National People’s Congress during its annual March meeting in 2012.

A disturbing development in 2011 for China’s 250 million registered users of microblogging services (“weibo”) was the introduction of the “real-name registration system.”[3] In December the Beijing municipal and Guangdong provincial governments, where major internet companies are based, announced that new users would be required to register for an account using their real names, with existing users expected to comply with this new requirement in the near future. This measure is probably one of the most effective yet in reining in the power of microblogs to expose rights abuses and put pressure on the authorities.

In December 2011, just days before the end of human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng’s five-year suspension of a prison term for subversion imposed in December 2006, a Beijing court cancelled the suspension and ordered him to serve his full three-year sentence in a Xinjiang prison. Disappeared for 20 months, Gao’s whereabouts remain unclear as he was not allowed to see his family when they tried to visit him in prison in January 2012. In December 2011 and January 2012, as the anniversary of the beginning of the Arab Spring approached, the government sent a clear warning that it would not tolerate any activities promoting democratic transition by imposing heavy custodial sentences on three democracy activists: Chen Wei, Chen Xi and Li Tie.

Ending 2011 on a slightly more positive note, in November the Guangzhou government announced “innovative reforms” intended to make it easier for certain categories of “social organizations” to legally register, with such reforms possibly being rolled out to the rest of China later. However, organizations which focus on the promotion of human rights are unlikely to benefit from such measures and will continue to suffer from close monitoring and forced closure.

Other key findings of this report

- In 2011, CHRD documented 3,833 incidences of individuals arbitrarily detained for their work in defense of human rights and 159 incidences of torture of such persons.

- Of this total, the vast majority were held in forms of detention with no basis in Chinese law or regulations,[4] particularly black jails and soft detention.

- According to a survey of 57 HRDs conducted for this report, one in four activists suffered torture or enforced disappearance; half were detained; and two out of three were monitored or harassed in 2011 for their activities.

About this report

CHRD’s fifth annual report on HRDs in China examines their situation China during 2011, the conditions in which their work was conducted, and the extent to which the government has or has not fulfilled its obligations to protect their rights as articulated in the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders[5] (hereafter referred to as “the Declaration”), which includes principles and rights already enshrined in other international human rights instruments and which are legally binding.[6] The report focuses on some of the key protections specified in the Declaration for individuals and groups working to promote human rights, such as:

- The right to freedom of expression (Articles 6 & 7);

- The right to freedom of assembly and association (Articles 5 & 13); and

- The right to an effective remedy for human rights violations (Article 9).

The report has been compiled based on a review of data gathered during 2011.[7] In addition, a survey was conducted with 57 human rights activists (53 males;14 females) based in 13 provinces and municipalities across China.[8] International and domestic media reporting and the work of other human rights organizations on the situation of human rights in China during 2011 were also consulted.

The report covers the period from January – December 2011. All events referred to occurred in 2011, unless otherwise stated. The report is not exhaustive in that it highlights only typical examples and key events that affected the conditions under which Chinese HRDs worked to promote human rights.

Content

- Introduction

- About this report

- Persecution of human rights defenders

- Arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance

- The use of torture and violence against HRDs

- Harassment of activists

- Freedom of expression

- Freedom of association and assembly

- Freedom of assembly

- Freedom of association

- Right to an effective remedy

- Recommendations

[1] The title of this report has become a symbol of how human rights defenders are being treated in China today. Before the ceremony to award the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiabo in December 2010, dissident author Yu Jie was dragged into a car, detained and tortured. After Yu was released, he was subjected to soft detention during “sensitive dates” throughout 2011. In January 2012 he and his family fled to the United States. In a statement released after his arrival, he described his ordeal, saying that a national security officer told him that “If the order comes from above, we can dig a pit to bury you alive within half-an-hour, and no one on earth would know.”

[2] Black jails are secret and illegal detention facilities; as well as being located in Beijing they are found across the country and are used by local governments to detain petitioners. For more information, see CHRD’s reports, “Black Jails: China’s Growing Network of Illegal and Secret Detention Facilities,” October 19, 2008, and “Black Jails in the Host City of the ‘Open Olympics’: Secret Detention Facilities in Beijing are Illegally Incarcerating Petitioners,” September 21, 2007.

[3] According to official figures by the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC), “ The 29th Statistical Reports on the Internet Development in China,” January 2012, http://www.cnnic.cn/dtygg/dtgg/201201/W020120116337628870651.pdf.

[4] These include black jails, soft detention, forced travel, detention in psychiatric institutions and other forms of deprivation of liberty which have no basis in law.

[5] The Declaration’s full name is the “Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms”.

[6] The previous four annual reports are: “Dancing in Shackles: A Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2007)”, April 30, 2008; “Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2008),” June 26, 2009; “Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2009)”, April 26, 2010; “Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China 2010,” March 2, 2011.

[7] These include news reports on CHRD’s Chinese website (http://wqw2010.blogspot.com/) as well as the press releases (Urgent Actions) and research reports on CHRD’s English website (www.chrdnet.com).

[8] The survey was conducted in November – December 2011. At least 10 HRDs in each of the following categories were surveyed: 1) those active in defending civil and political rights; 2) those active in defending economic, social and cultural rights; 3) those who have had more than 10 years experience as rights activists; 4) those who have between 5 – 10 years experience as rights activists; and 5) those who have fewer than 5 years experience as rights activists.