China: Repeal Overseas NGO Law & Protect Freedom of Association

Comments Off on China: Repeal Overseas NGO Law & Protect Freedom of Association

China’s New Overseas NGO Management Law Strangles Civil Society

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders – April 28, 2016) – CHRD denounces the Chinese government’s adoption of a draconian law on overseas NGOs that will have a profoundly detrimental impact on civil society in China. The law passed China’s rubber-stamp legislature on Thursday despite critical international responses to the most recent draft that dates back to last spring. The adopted version appears to retain the most troubling elements of the previous draft, and allows for even tighter government control over NGO activities. Once the law takes effect on January 1, 2017, it will further restrict international NGOs working in China and suffocate the country’s already beleaguered independent organizations.

As written, the law has kept perhaps the most worrisome provision, which hands the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) full authority over the registration and supervision of foreign-based NGOs operating inside China. This is a clear indication the government views such groups as a threat to national security. The law has also retained the strict funding restrictions that appeared in the previous draft. As such, the legislation will deliver a heavy blow to mainland NGOs, which rely heavily on overseas NGOs’ financial support due to insurmountable obstacles to securing funding inside China. CHRD calls for the repeal of the overseas NGO management law or, at minimum, significant revisions of its stipulations that violate independent groups’ right to freedom of association.

The National People’s Congress Standing Committee adopted the legislation on April 28 following its third reading during its bi-monthly session, according to the state media agency Xinhua. The law’s official name has been changed to the Overseas NGOs’ Domestic Activities Management Law (境外非政府组织境内活动管理法). At the time of writing, the text of the law had not been made public, but the limited state media reporting on the third draft, which appeared prior to the vote, seemingly confirms that the government has not relented on the most troubling aspects in the widely circulated second draft. That draft (Chinese // unofficial English translation) alarmed the international community, and sparked significant concerns due to its focus on national security and its overly broad scope.

Among the changes in the legislation, as reported by Xinhua prior to today’s vote, the four below are the most alarming, as they authorize even greater power to police (compared to the prior draft) to exercise “daily supervision and monitoring” of overseas NGOs:

- Police can end foreign NGO organized activities that they deem to “endanger national security.” If police suspects that a “temporary activity” organized or sponsored by an overseas-based group will threaten “national security,” police can order the Chinese co-organization to halt it, with no apparent process to challenge the police’s decision. The law does not clearly define the activities that “endanger national security” and other laws, such as the National Security Law (2015) and the Criminal Law (1979, amended 2015) also fail to provide an adequate definition. The lack of a definition will contribute to arbitrary decision-making by police.

- Police can put foreign NGOs on a “blacklist” if police allege that they engage in behavior that “endangers national security.” Under the new law, the State Council and organs of public security reportedly have the authority to create a list of “unwelcomed” overseas groups that engage in activities deemed illegal, such as “subversion of state power” or “separatism.” This stipulation allows police to create a de facto “blacklist” of international NGOs that will no longer be allowed to establish representative offices or conduct temporary activities inside China.

- Police can bring in for questioning the chief representative of international NGOs (or other “responsible” persons) at any time for any reason. Police have long wielded the power to question representatives or staff of Chinese NGOs—with or without legal summons—often as a way to issue warnings or simply to intimidate. This addition to the law further extends police capacity to intrude upon the work of overseas NGOs inside China and harass those involved with them. Giving police even more oversight, the new law retains the stipulation in the earlier draft allowing them the power to collect all materials pertaining to activities that overseas organizations carry out in the country.

- Police can more closely monitor overseas NGOs’ funding sources and expenses. Another change to the second draft, which has the chilling effect of intimidation, is the stipulation that overseas NGOs working in China must make full public disclosure of their funding sources and expenses. The previous draft only required that local accountants conduct audits of submitted financial reports. This change will put the finances of foreign groups under even closer scrutiny by authorities, which are already closely monitoring foreign NGOs’ funding support to Chinese groups.

These expansions of police power underscore an essential function of the law—to restrict foreign influence and ideas from entering China, especially when the government perceives that they present a political threat or would offer different perspectives on human rights and other sensitive issues. In March 2015, in commenting on the second draft, an NPC spokesperson unequivocally stated that the law was needed “for safeguarding national security and maintaining social stability.” Under President Xi Jinping, the application of “endangering national security” crimes has been vastly expanded, and allegations of such crimes have been repeatedly used to target civil society groups, human rights activists, and government critics. For instance, police have used crimes of “endangering national security” to arrest and hold incommunicado human rights lawyers and civil society activists seized in the “709” crackdown last summer. Authorities also cited “endangering national security” as the reason to detain and deport Swedish human rights worker Peter Dahlin in January 2016.

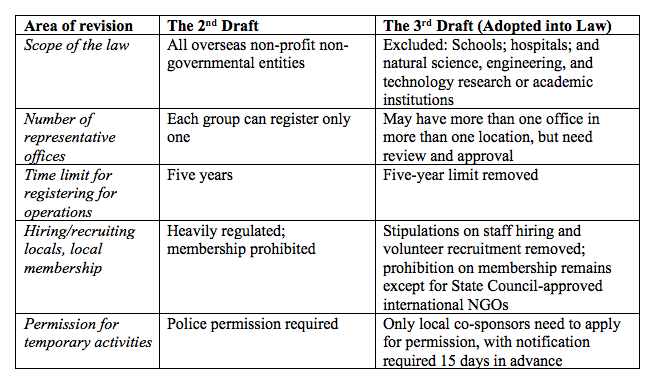

While the third draft appears to grant a few concessions that are said to “facilitate” services and “simplify” procedures for foreign NGOs, such changes are mostly minor, and they also lack specific parameters, which was a major issue with the previous draft. The table below summarizes some concessions that Xinhua reported were made in the 3rd draft that was passed into law on April 28, 2016 (see more details after table).

- The scope of law was reportedly narrowed to exclude “foreign schools; hospitals; and natural science, engineering, and technology research or academic institutions; and other entities” that have academic exchanges or cooperative programs with counterparts in China, which will be subjected to jurisdiction of other existing laws. As such, according to Xinhua, the law now reportedly covers “not-for-profit, non-governmental social organizations such as foundations, social groups, and think tanks.” However, it is unclear if the reported list of groups governed by this law is exhaustive, or may instead leave room for authorities’ discretion to make exceptions. It is not known if churches and sports clubs, which are normally registered overseas as non-profit and non-governmental organizations, fall under the scope of the law.

- Foreign organizations can apply to set up more than one representative office in different locations in China, a change from the previous limit to a single one. However, authorities must review and approve the locations and numbers of such offices.

- The new law removes the five-year time limit included in the previous draft on overseas organizations’ representative offices operating in China. Police retain the power to suspend, cancel, or revoke the registration of NGOs that engage in illegal activities at any time.

- The new law removes a provision in the previous draft that heavily regulated overseas NGOs’ hiring of staff or recruiting volunteers in China. It is not clear if the law retains the provision requiring overseas NGOs from reporting employee information to public security bureaus. The law also clarified that, with the exception of overseas organizations approved by the State Council, any overseas NGO that registers a representative office or holds temporary activities in China is prohibited from recruiting members in China. In other words, Chinese citizens are banned from becoming members of such NGOs.

- The new law simplified procedures for holding temporary activities by those overseas NGOs that have not registered representative offices in China. The previous draft requires them to apply for permits from the police. The new law only requires their Chinese co-sponsoring institutions to apply for government permission and notify local authorities 15 days in advance of activities. The law still does not appear to specify what constitutes an “activity,” an ambiguity, deliberate perhaps, which has come under heavy criticism. Police still retain overreaching authority to block activities as threats to “national security.”

With the passage of the Overseas NGOs’ Domestic Activities Management Law, CHRD issues the following recommendations:

- The law must be repealed until significant revisions of the legislation are made to conform with international human rights standards on the protection of the right to free association.

- Governments and the European Union with bilateral human rights dialogues with China must raise serious concerns during such dialogues and in all meetings with high-level Chinese officials over the passage of this law, as well as the government’s new standard of using the pretext of “national security” to persecute civil society organizations and stifle human rights activities.

- CHRD calls on the Member States of United Nations Human Rights Council, at its 32nd Session this summer, especially those who recommended China to respect freedom of association and protect civil society during the 2013 UPR, to urge China to repeal this draconian legislation and end crackdowns targeting civil society, as such acts do not conform to HRC Resolution 27/31.

Contacts:

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Research Coordinator (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD