Earth Day: China Must Protect Human Rights To Effectively Protect the Environment

Comments Off on Earth Day: China Must Protect Human Rights To Effectively Protect the Environment

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, April 20, 2017) – The Chinese government must protect human rights to make meaningful progress in environmental protection. Basic rights like freedom of expression, assembly, association and press are fundamental to any genuine attempt to effectively respond to serious threats to the environment and public health, CHRD said today, to mark this year’s Earth Day on April 22.

The scale of environmental problems and the challenges are daunting: China has several of the world’s most polluted cities and, according to a Chinese academic study, about one-third of deaths in the country can be linked to toxic smog. Yet despite the Chinese government’s declaration of “war” on pollution, authorities are still fearful of open debates and public discussions, as was evident when government censors blocked the viral documentary film “Under the Dome” in 2015.

The government’s escalating suppression of civil society and human rights activities makes Chinese citizens vulnerable to persecution for expressing concerns about the environment to their government, for peacefully demonstrating against polluting infrastructure and commercial projects, or just working for environmental groups. The lack of government accountability; lax implementation and weak enforcement of laws and regulations; limited public participation in decision-making; suppression of environmental activists; insufficient transparency and access to information; and constrained access to justice are some of the systemic roadblocks to any efforts for China to meet the substantive and procedural obligations to clean up the environment, cut down carbon emission, and protect the rights of its citizens to clean air, water, and health.

Chinese authorities have been building an environmental protection regulatory framework, but deficiencies, loopholes, and lax implementation and enforcement hinder effective efforts and meaningful results. While authorities put out numerous laws and regulations, most notably the revised Environmental Protection Law in 2014, and the Air Pollution Control Law and Environmental Impact Assessment Law in 2015, loopholes remain and the regulatory framework is still not comprehensive, including the lack of a soil pollution law. In addition, complex implementation and enforcement deficiencies, sometimes due to lack of capacity but often fueled by protectionism and corruption, continues to pose huge challenges. In one recent example, a Ministry of Finance report in December 2016 found that hundreds of millions of Chinese dollars (RMB) from a central government fund to fight air pollution had been embezzled and misspent in several provinces. In other examples, in 2015, the former vice minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection was expelled from the Chinese Communist Party for issuing fake quality control certificates; and a national survey found that 173 steel plants were found to have violated environmental regulations, including at least one that local authorities failed to shut down despite repeated requests from higher-level environmental authorities.

Like other activists and independent groups, Chinese environmentalists and their organizations have been targeted in the clampdown on civil society under President Xi Jinping’s rule. NGOs working on environmental issues face new hurdles in their work because of the recently issued laws on overseas NGOs and domestic charities, which will likely further restrict funding for domestic NGOs. The new Law on the Management of Domestic Activities of Overseas NGOs reflects the government’s obsession with the perceived threats of “foreign influences” and “national security,” which some authorities may have taken as a signal to escalate suppression of all NGOs, including environmental groups. In one example, Chongqing activist Xue Renyi (薛仁义), the head of the group Green Leaf Action, was taken in for police questioning last December. Police reportedly warned Xue that his organization was being “controlled” and “manipulated” by “foreign forces,” and said that his group’s demands for food safety, clean air and water, and other health safeguards constitute “illegal activities.” Before founding his group in early 2016, Xue had been harassed by authorities for his long-time promotion of environmental protection.

In another case, Ms. Liu Shu (刘曙), the head of the NGO Shuguang (or “Dawn”) Environment in Changsha City in Hunan, was given a 10-day administrative detention in October 2016. The punishment was likely retaliatory for her group’s publicizing of pollution data collected through its own investigation, including on dangerous levels of heavy metals in Dongting Lake. Authorities charged Liu with “releasing state secrets related to counterespionage work.” For years prior to Liu’s detention, authorities had put pressure on her group because of their campaigns for compensation and redress for victims of environmental pollution.

The Chinese government has refused to release its carbon emissions calculations to the United Nations since 2005, making it difficult to independently verify its claims on carbon reduction. Furthermore, available data that the government has released may have been falsified by local officials or companies. Environmental protection officials in Xi’an were found to be falsifying air pollution data in October 2015, despite a crackdown on false data announced in April of that year by the vice minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection. In early 2017, inspectors from the ministry found 3,000 factories in northern China that had falsified emissions data, where local officials did not enforce legislation and issue fines.

The lack of data poses one of the serious challenges for environmental protection efforts. For instance, unavailable data on soil pollution has compounded problems with getting soil pollution remediation off the ground. Failing to make data on water pollution public has resulted in confusing policy responses and public distrust. Authorities often do not sufficiently disclose information about environmental issues when individuals or groups submit requests through China’s opaque “open government information” system, including information related to tap and rural drinking water monitoring tests and ecological projects. With little trust in government data and the lack of an independent press watchdog, it is difficult for international monitoring agencies, civil society groups, and concerned Chinese citizens to independently monitor any efforts taken by the government and assess the effectiveness of policy measures.

Furthermore, the government has recently adopted new laws and rules that further restrict communications, granting authorities greater control over the flow of information online, and allowing increased criminalization of speech that authorities deem threatening. In one incident, Internet writer Liu Ermu (刘尔目) was criminally detained in December 2016 after he posted an essay on WeChat criticizing authorities’ responses to activists who brought attention to dangerous smog levels in and around the Sichuan city of Chengdu. Activists had staged peaceful sit-ins and put face masks on public statues, prompting police to seal off a city square, detain protestors, and force stores to report any large purchase of face masks. In addition, the provincial propaganda office instructed the media to censor and “shape” coverage of the smog. Let go after less than a day in custody, Liu posted an account online of his interrogation by police, and decried the authorities’ treatment of environmental activists as “criminals.”

Legal channels for victims of environmental pollution to seek justice have expanded over the last few years, but these channels remain ineffective. The revised Environmental Protection Law for the first time allowed NGOs to file public interest litigation, but very few NGOs have been able to file cases in court; the number of such NGO-led cases heard by courts, as of April 2017, stood at approximately 110, and courts reportedly remain hesitant to accept these types of cases. The lack of independent judicial oversight hinders efforts to seek environmental justice through the judicial system. In one ongoing case, a group of human rights lawyers, including Cheng Hai (程海) and Yu Wensheng (余文生), filed lawsuits against the cities of Beijing and Tianjin and Hebei Province last December, accusing authorities of failing to protect their residents from air pollution. The government’s reaction has been strident: judicial personnel have pressured some of the lawyers to drop the lawsuit, and media censors banned press coverage and public discussion of the case. Beijing authorities indicated in March that the case would not go to court.

Protests over environmental issues have been among the major reasons for the tens of thousands of demonstrations in the country each year. While in some cases, authorities capitulate to demands in the face of public anti-pollution protests, the routine responses from authorities involve the use of police force to break up protests and criminally detain protesters. Over one thousand police in Xi’an crushed a rally by residents opposing a proposed waste incinerator plant in October 2016. Police beat up demonstrators and reportedly detained hundreds of them. Government censors scrubbed clean social media messages about the protest and its aftermath, and barred news organizations from covering the story. In Inner Mongolia, police put down environmental protests last year over pollution from smelter and aluminum plants. Hundreds of people including ethnic Mongolian herders had demonstrated against what they believed to be the sources of air pollution and health hazards, citing the death and deformity of sheep on nearby grasslands.

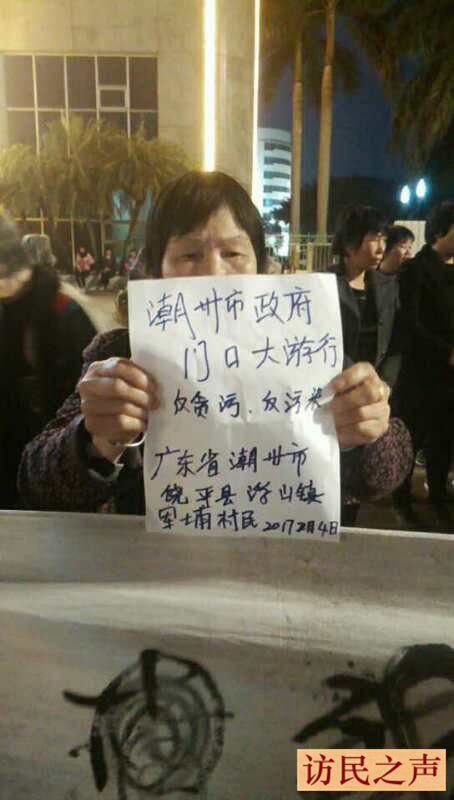

Four villagers in the Guangdong city of Chaozhou were recently arrested after protesting local environmental problems.

Most recently, Guangdong police arrested four demonstrators in April for their role in a protest over environmental pollution. Chen Ruifeng (陈瑞峰), Mai Pinglin (麦平林), Mai Yingqiang (麦应强), and Wang Er (王而) are under arrest on suspicion of “gathering a crowd to disrupt order of a public place and to disrupt traffic” for their role in a protest in Chaozhou City. Police violently broke up a demonstration of over 100 local villagers as residents protested over a polluting battery recycling plant and the construction of other factories. The protest only began after local cadres ignored villagers’ calls to either shut down the recycling plant or resolve the pollution issues.

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights expressed concern in its 2014 Concluding Observations over inadequate implementation and monitoring of new measures to mitigate ecological degradation. The Committee called on China to adopt all necessary measures to enforce its regulations, impose necessary sanctions, and provide adequate compensation to victims in order to comply with its obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

CHRD urges the Chinese government to protect the right to peaceful assembly, including to demonstrate against environmental problems, and to establish more reliable channels through which citizens may voice their environmental concerns; repeal or amend existing rules and regulations that limit free speech and communications, and allow free and open discussion about environmental issues; and allow environmental NGOs and environmentalists greater space, in which to work and associate, and improve NGO access to all funding sources, including international sources.

Contacts:

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Researcher (English), +1 628 400 7198, victorclemens[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD