Draft Intelligence Law Portends Further Squeeze on China’s Civil Society

Comments Off on Draft Intelligence Law Portends Further Squeeze on China’s Civil Society

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, May 24, 2017) – Provisions in China’s new draft intelligence law, if adopted in their current form, would authorize pervasive surveillance on NGOs and intrusion on privacy. The draft law requires all Chinese citizens to collaborate with national intelligence collection; authorizes Chinese intelligence agents overseas to use “the necessary means” in their work; and requires intelligence agencies to collect and process information on foreign groups and individuals operating in China that allegedly fund, incite or implement acts that “endanger national security,” or domestic groups or individuals “colluding” with foreigners inside China. The draft intelligence law clearly aims at further tightening control over civil society organizations, both domestic and international, which are already under assault as “hostile forces” that threaten “national security.”

The National People’s Congress (NPC) released the draft of the National Intelligence Law on May 16, 2017, and it is open for public comments until June 4. From that time, there will be a second reading of the bill by the NPC, a largely rubber-stamp parliament, and it may then be adopted. A selected “explanation” of the draft law has been released on the NPC website, with a full draft posted online on a separate website.

Though the draft law contains language about “respecting and protecting human rights” in national intelligence work (Article 7), it is replete with provisions authorizing the expansion of the power of state intelligence agencies to conduct surveillance of NGOs. It joins the phalanx of recently adopted Chinese laws that tighten the government’s grip on civil society, including the Counter-Espionage Law (2014), National Security Law (2015), Counter-Terrorism Law (2015), Overseas NGO Law (2016), and Cyber-Security Law (2016). In releasing the draft law, the NPC explicitly stated that authorities should work to properly coordinate these laws.

CHRD has serious concerns over the following draft provisions:

- Reference to vaguely defined “threats” to “national security”: Article 2 of the draft law requires that national intelligence work to “prevent and mitigate threats endangering national security,” a term vaguely defined in Chinese law. Authorities can arbitrarily cite such concerns to criminalize human rights activities or NGOs. The definition in the National Security Law is extremely broad, and the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights expressed concern that the law “leaves the door wide open to further restrictions of the rights and freedoms of Chinese citizens.” Certain crimes fall under the category of “endangering state security” in the Criminal Law (Articles 102-112), but Ministry of Public Security regulations from 2013 have permitted police to broadly designate other crimes as endangering national security. Chinese citizens have been accused of endangering national security for documenting human rights violations, performing their professional duties as lawyers, expressing their thoughts and opinions, working as journalists, commenting on government policies, or forming political parties. If the National Intelligence Law is adopted as drafted, foreign and Chinese NGOs, human rights activists, lawyers, journalists, and dissidents, as well as schools, companies, and other institutions, could face further surveillance and criminal prosecution under a pretext that they “endangered national security.”

- Vast authority to violate privacy: The draft law gives national intelligence agencies broad authority to question anyone, read or collect any material (Article 15), and install surveillance devices or set up on-site posts inside any office or commercial buildings (Article 16). It is unclear which body will scrutinize requests and grant approval or monitor such expansive surveillance tactics and intrusion on privacy. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China has signed but not ratified, protects everyone from arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy (Article 17).

- Authorization of intelligence agencies operating overseas to use “the necessary means” in their work: The draft law gives Chinese intelligence agencies broad powers to operate beyond mainland China, by authorizing the use of “the necessary means, tactics, and channels” to carry out intelligence work domestically and overseas (Article 9). There is no clear limit on what is “necessary for their work,” allowing Chinese security agents to conduct operations to target foreign and Chinese nationals abroad. In recent years, Chinese security forces have already targeted government critics overseas. For example, Chinese agents working with local counterparts or on their own: abducted a Swedish national in Thailand in October 2015, kidnapped a British bookseller in Hong Kong in December 2015, and tracked down the wife and daughters of a detained lawyer in Thailand in February 2017.

- Targeting of foreign and Chinese groups and individuals: Under Article 10 of the draft, intelligence operations “must” collect information on foreign groups or individuals in China that are suspected of funding, inciting or implementing acts that “endanger national security,” or domestic groups or individuals “colluding” with foreigners inside China involved in such acts. Article 11 says that acts that endanger national security “must” be held accountable to the law, and that intelligence work will be the basis for “preventing, prohibiting, and punishing” such behavior. Lacking clear parameters of what constitutes “endangering national security,” these two provisions could be used to arbitrarily target overseas NGOs or individuals and Chinese citizens working with overseas NGOs. The Chinese government has targeted foreign nationals on charges of “endangering national security” with dubious evidence, including the detention and deportation of a Swedish human rights worker in January 2016, the conviction and deportation of an American businesswoman for “espionage” in April 2017, and the ongoing detention since March of Taiwanese national Lee Ming-cheh.

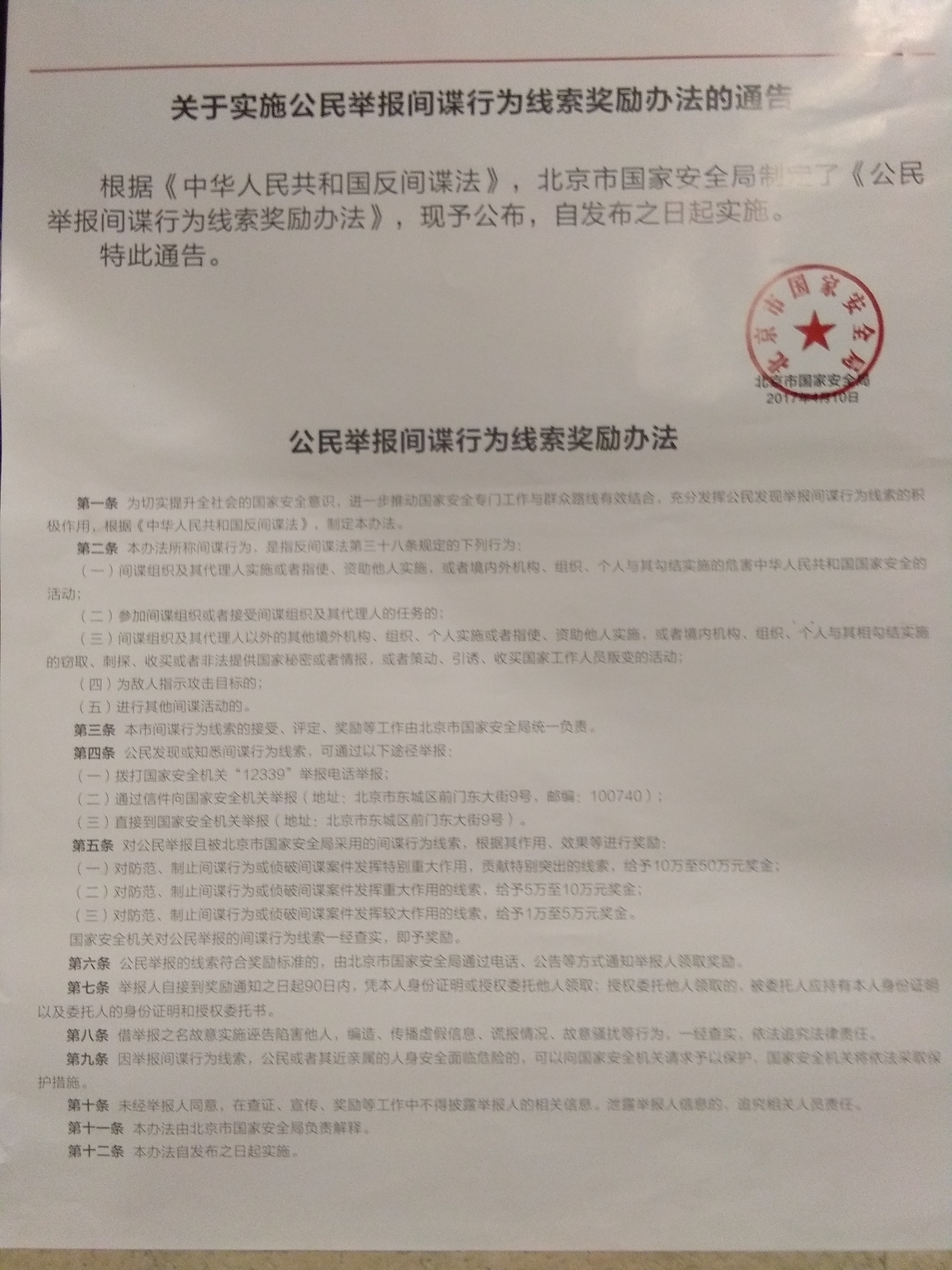

- Nationwide mobilization for surveillance collaboration: The draft law would require all state organs, armed forces, political parties, social groups, enterprises, public institutions, organizations and citizens in China to “support, assist and coordinate with” state intelligence agencies and keep secret such collaborations (Article 6). The draft law also makes intelligence collection and collaboration an obligation of all relevant departments at all levels of government, enterprises, public institutions and other organizations or citizens (Article 13). This would potentially create a vast and intrusive system, where every citizen is bound by law to collaborate secretly with state intelligence agencies; one can otherwise face a 15-day administrative detention or criminal prosecution (Article 25). Following the 2015 adoption of the National Security Law, the government launched a National Security Education Day to be held on April 15 each year. In 2017, it was used to launch a program to reward up to 500,000 RMB (72,000 USD) in cash for unmasking foreign spies, and in 2016 to warn Chinese women of the “dangers” of dating foreign men who may be spies, with posters appearing all over Beijing.

In its current draft form, the intelligence law further infringes the rights to free expression, association, and peaceful assembly in China. President Xi Jinping has escalated his crackdowns on civil society and prosecuted lawyers and activists for promoting and protecting human rights as “endangering national security.” International NGOs operating in China have been treated as “hostile foreign forces.” According to CHRD’s documentation, almost one-third of imprisoned human rights defenders since 2013 were convicted with “endangering state security” crimes. By putting out yet another law legalizing surveillance and persecution of human rights defenders in the name of national security, China continues to defiantly ignore UN Human Rights Council resolution (HRC 27/31), which calls for the “creation and maintenance of a safe and enabling environment for civil society.”

CHRD urges the NPC to drop or revise key provisions in the National Intelligence Law to ensure protection of Chinese citizens and foreign nationals’ human rights. International organizations, foreign NGOs, and like-minded governments should submit comments on the draft law, and raise concerns with officials at all levels of the Chinese government.

Contacts:

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Researcher (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD