China Must Release Wu Gan & Stop Treating Free Speech as an Act of Subversion

January 4, 2018 Comments Off on China Must Release Wu Gan & Stop Treating Free Speech as an Act of Subversion

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, January 4, 2017) – The lengthy prison sentence recently given to activist Wu Gan (吴淦) is a blatant violation of his universal right to free expression and peaceful assembly. CHRD calls on the Chinese government to immediately and unconditionally release Wu. The Tianjin No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court handed down an eight-year prison sentence for “subversion of state power” on December 26 following an August trial. Wu Gan’s case has been rife with abuses of his due process rights, including his right to legal counsel and the right to a fair and open trial. Wu has also reportedly been subjected to torture in failed efforts by authorities to extract a confession.

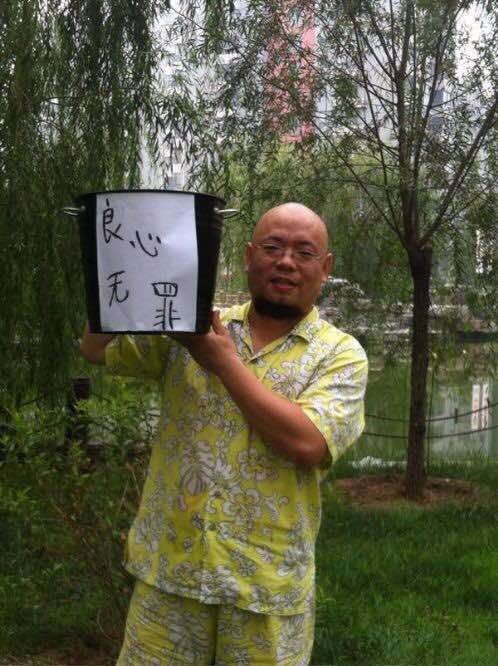

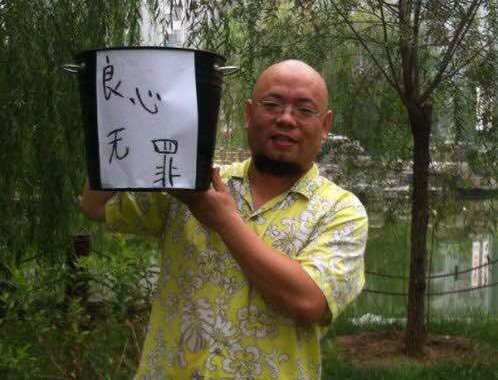

Wu Gan, whose advocacy had combined spirited online speech, satire and humor, and street performance, has vowed to appeal his conviction and punishment. An official government summary of the verdict stated that Wu had “used ‘rights defense’ and ‘performance art’ as a “ploy” to “seriously harm national security and social stability,” and that he had “used the internet to disseminate voluminous statements attacking state power and the constitutionally established state order.”

Wu’s sentence is the longest to date issued to anyone tied to the 709 Crackdown targeting China’s human rights lawyers. Lawyer Zhou Shifeng (周世锋) is serving a seven-year sentence and activist Hu Shigen (胡石根) a 7.5-year punishment, after being convicted in August 2016. Shortly before Wu was detained in May 2015, he had started working with Beijing Fengrui Law Firm, the main target of the crackdown, and where Zhou had served as director.

Case defined by rampant rights violations

Wu Gan has been a victim of injustice and mistreatment at each step in his case, from his initial detention and through his trial and sentencing. Authorities denied Wu access to legal counsel for long stretches of time during his detention. His first visit with his lawyers, Yan Xin (燕薪) and Ge Yongxi (葛永喜), occurred on December 9, 2016—nearly 19 months after he was taken into custody. Wu had been held for 27 months by the time he was finally tried on August 14, 2017, an unreasonably prolonged pretrial detention.

Wu’s August trial and December sentencing were closed to the public, and police blocked and harassed individuals who wanted to gather at courthouses to support the activist. Police reportedly questioned and briefly detained several individuals who had gone to Tianjin in anticipation of the hearing in December. Authorities forcibly sent many back to their hometowns, where police kept them under close watch to prevent them from returning to Tianjin. Prior to the trial in August, authorities declared proceedings would be held behind closed doors because the case involved “state secrets.” Wu Gan’s father, Xu Xiaoshun (徐孝顺) was even prevented from attending the trial by national security officers. There was a heavy police presence outside the courthouse during the trial, and officers reportedly detained over a dozen individuals.

Wu made several allegations that he was tortured and mistreated during his detention. At the December 2016 meeting with his lawyers, Wu alleged that police had physically and psychologically tortured him in an effort to make him to confess to crimes, but that he had refused. Lawyers Yan and Ge filed a complaint to prosecutors in Tianjin over the alleged mistreatment, which included sleep deprivation, exposure to extreme cold, extended interrogations, limits on activities outside his cell and in fresh air, and having his hands cuffed and feet shackled. Wu said that one officer threatened to drive to Wu’s daughter’s school to harass her and make his family resent him, and a police investigator made veiled death threats against Wu’s family. The complaint also alleged that Wu was hospitalized unnecessarily to “create psychological pressure.” In 2017, Wu made further accusations, including that Wu’s back injury, which had been caused in detention, and high blood pressure were not being adequately treated. Wu reportedly told lawyer Ge in March 2017 that psychologists had given him “counseling,” with the apparent aim of persuading him to plead guilty.

Wu Gan had stressed his innocence in a statement released via his lawyers before his August 2017 trial. The statement read in part: “I will be convicted not because I am guilty, but because of my refusal to accept a government-appointed lawyer, to plead guilty in a televised propaganda confession, and because I exposed torture, mistreatment, violence, and prosecutorial misconduct.”

Wu’s refusal to confess may have factored into his harsh sentence. On the same day that Wu was sentenced, a Hunan court convicted lawyer Xie Yang (谢阳) of “inciting subversion of state power.” The court “exempted” Xie from punishment, however, stating that he had admitted at trial to criminal behavior and “expressed regret.” It is believed that Xie’s statements, including his “confession,” were issued under coercion and in exchange for “leniency.” Though not sent to prison, Xie continues to face retaliation, including constant monitoring by police officers living next to his home.

Wu Gan should be released, and should never have been detained in the first place, based on standards in international law and principles in China’s constitution. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the country’s constitution protect the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association, as does the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which China has signed and signaled it will ratify. The Human Rights Council has in the past stressed the “need to ensure that the invocation of national security…is not used unjustifiably or arbitrarily to restrict the right to freedom of opinion and expression…,” including “discussion of government policies and political debate.”

Background of criminal case & rights advocacy

Wu Gan was initially seized on May 20, 2015, outside a courthouse in Nanchang City in Jiangxi, where he had gone to support rights lawyers working on a death penalty case involving defendants who claimed they had been tortured to confess. After Wu served a 10-day administrative detention, police from Fujian criminally detained him on May 27 on suspicion of “libel” and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” In July 2015, the Xiamen City People’s Procuratorate approved Wu’s formal arrest for “picking quarrels” and “inciting subversion.” In January 2016, Wu’s case was transferred to Tianjin, where many other 709 Crackdown detainees were being held, and police re-started the period of investigation on his case, claiming that new evidence had emerged. On January 3, 2017, authorities at the Tianjin No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court confirmed that Wu had been formally indicted.

Prior to his current detention, Wu Gan, widely known by his screen name “Super Vulgar Butcher” (超级低俗屠夫), or “The Butcher” (屠夫) for short, had been detained, threatened, and interrogated many times for his human rights activism. A military veteran, Wu later worked as a security guard at the Xiamen Gaoji International Airport for over a decade. He resigned in 2008 and turned to blogging and activism. In 2009, Wu became well-known for his campaigns on several high-profile cases, such as that of waitress Deng Yujiao (邓玉娇), who killed a government official who tried to sexually assault her in Hubei, and a forced confession case in Kunming in Yunnan Province, when police accused a father of prostituting his middle school-aged daughters. Wu’s father, Xu Xiaoshun, has also faced persecution as a form of “collective punishment.” Xu was detained in Fuzhou in 2013 and held for seven months before being released on bail. He was seized a month after Wu Gan was detained in 2015, and tried on charges of “evading official duties” in March 2016.

Contacts

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012, reneexia[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Researcher (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083 franceseve[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD