China Strips Rights Lawyers’ Licenses in Reprisal Against Their Push for Rule of Law

January 24, 2018 Comments Off on China Strips Rights Lawyers’ Licenses in Reprisal Against Their Push for Rule of Law

(Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders – January 24, 2018) – Judicial authorities in China have stripped several human rights lawyers of their licenses to practice law in recent months, detaining one of them just days ago, in clear retaliation against the lawyers for defending their clients’ legal and human rights. These latest incidents amount to another wave of suppression against lawyers who have spoken out about government interference in the judiciary. As such, the cases signal that the Xi Jinping government is not letting up on its assault on lawyers’ independence and continues to backtrack on its own promises to “rule the country with law.”

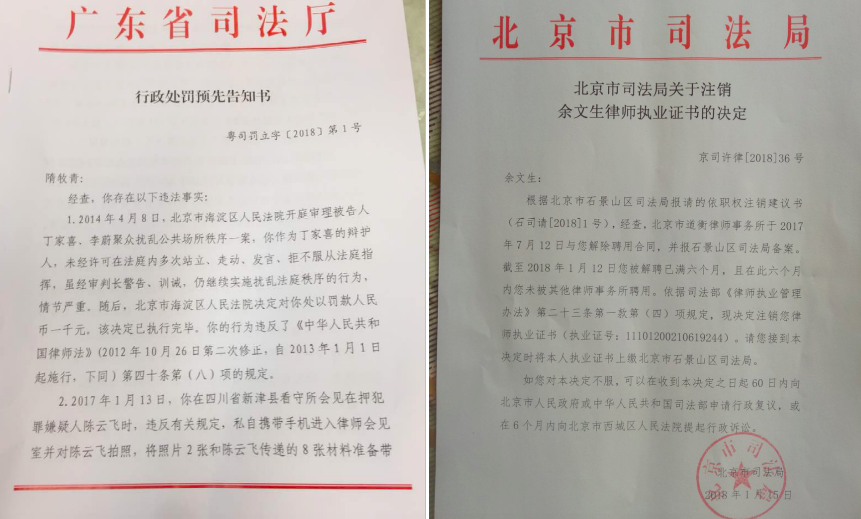

Lawyers Sui Muqing and Yu Wensheng are among the rights lawyers who have recently been stripped of their licenses to practice law.

Police seized lawyer Yu Wensheng (余文生) outside his home in Beijing on January 19, just three days after his license to practice law had been de-registered (注销), or “cancelled” temporarily, by the Beijing Municipal Justice Bureau. Yu is being held at Shijingshan Detention Center on suspicion of “obstructing official duties.”

On January 22, lawyer Sui Muqing (隋牧青) was summoned and given a notice by Guangdong Provincial Justice Department officials stating that his license to practice law has been revoked (吊销). The notice cited Sui’s online speech—in which the lawyer had defended his clients’ legal rights and revealed torture allegations—as evidence that Sui had breached China’s Law on Lawyers. Revoking a lawyer’s license bans a lawyer from ever practicing law again. Lawyer Sui was given three days to argue his case. The notice from the Guangdong officials cited Sui’s public criticism of authorities’ mishandling of the cases of Sichuan activist Chen Yunfei (陈云飞) in 2017 and Beijing-lawyer Ding Jiaxi (丁家喜) in 2014. Sui had protested unlawful court proceedings during Ding’s trial and publicized online Chen’s accusation of torture at the detention center.

The notices lawyers Sui Muqing and Yu Wensheng received from judicial authorities stripping them of their law licenses.

In another recent case, the Hangzhou City Justice Bureau suspended the practice of lawyer Wu Youshui (吴有水) for nine months on December 28, 2017, stating that his comments on social media had “endangered national security” and constituted “vicious defamation.” As the basis for suspending lawyer Wu Youshui’s license, judicial authorities in Hangzhou cited his Weibo account posts that mocked “corrupt officials,” including Xi Jinping, and the government’s persecution of fellow lawyers. Lawyer Wu argued in defense of his client that monitoring speech on the messaging tools WeChat and QQ is unlawful and violated free speech rights. Wu’s comments seemed to directly trigger the nine-month suspension of this license.

In addition, in early September, the Shandong Provincial Justice Department revoked the license of lawyer Zhu Shengwu (祝圣武), declaring that his online expression had “endangered national security” and disparaged the socialist system. Authorities gave Zhu three days to request a hearing, which he did, but authorities upheld the original decision.

In the days before being put under criminal detention, Yu Wensheng had been disbarred, denied permission to set up a law firm, and banned from travelling overseas on “national security” grounds. He had also released a statement calling for Constitutional and legal reforms. State media outlets released an edited video after lawyer Yu was detained, and claimed Yu had physically attacked police who were trying to take him in for questioning on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” The Beijing Municipal Judicial Bureau cited lawyer Yu’s lack of employment at a law firm for the past six months to justify “de-registering” his license. In July 2017, Beijing Daoheng Law Firm dismissed Yu under pressure from judicial authorities, who had refused to let Yu Wensheng and the law firm’s director, Liang Xiaojun (梁小军), “pass” the annual license review. That punishment was likely in reprisal for Yu’s dogged attempts to visit his client, detained lawyer Wang Quanzhang (王全璋), who remains the only lawyer still held in pre-trial detention from the July 2015 crackdown.

These latest incidents of stripping law licenses signal Chinese authorities’ determination to punish human rights lawyers not cowed into silence by the “709 Crackdown.” Lawyer Sui Muqing spent six months in “residential surveillance at a (police-) designated location” (RSDL) in 2015. But after his release in January 2016, he returned to work and continued to defend human rights lawyers and activists. Lawyer Yu Wensheng has not backed down from exercising his right to free speech, having sued the government over its failure to eradicate air pollution and to provide compensation for torture victims.

Lawyers linked to the 709 Crackdown continue to pay a heavy price. Some remain in detention and others have been given prison sentences, and they have often been charged with crimes of “endangering state security.” Lawyer Wang Quanzhang, being held for “subversion of state power,” has now disappeared into police custody for nearly two-and-a-half years, or since he was first detained in August 2015. Lawyer Zhou Shifeng (周世锋) is serving seven years for “subversion” after he was convicted in August 2016. Lawyer Jiang Tianyong (江天勇), a vocal supporter of other persecuted lawyers, was given a two-year sentence for “inciting subversion” in December 2017. More recently, lawyer Li Yuhan (李昱函) has been detained since last October on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” for her steadfast advocacy efforts for lawyers and their families affected by the crackdown. Lawyer Li Heping (李和平) was convicted of “subversion” in 2017, thus barring him from practicing law again, though he was given a suspended sentence.

China’s ongoing persecution of human rights lawyers continues to violate international human rights standards, which lay out protections for the exercise of fundamental rights and for the independence of lawyers. The Universal Declaration on Human Rights guarantees the right to a fair trial (Article 10), freedom of thought, conscience, and religion (Article 18), freedom of opinion and expression (Article 19), freedom of peaceful assembly and association (Article 20), and freedom of just and favorable conditions of work (Article 23). International norms on the basic principles of lawyers emphasize that governments should ensure that lawyers are not discriminated against based on their political views (Article 10) and are able to perform all of their professional functions without interference (Article 16). Lawyers also have the same rights as citizens to freedom of expression, belief, assembly, and association (Article 23). The UN Human Rights Council, a body of which China is a member, stressed in June 2017 that an independent legal profession is one of the “essential prerequisites for the protection of human rights.”

The UN Human Rights Council, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, the EU, and countries striving for the rule of law must urge the Chinese government to release all lawyers detained in violation of their human rights and to end the use of administrative measures to bar the practice of law by human rights lawyers.

Contacts

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 863 866 1012

reneexia[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Researcher (English), +1 209 643 0539

victorclemens[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Researcher (English), +852 6695 4083

franceseve[at]nchrd.org, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD