Zero Tolerance for Human Rights Defenders in the Year of “Zero COVID”: Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2021)

March 7, 2022 Comments Off on Zero Tolerance for Human Rights Defenders in the Year of “Zero COVID”: Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2021)

Executive Summary

Throughout 2021, the Chinese state continued to tighten control over nearly all facets of society, often under the pretense of controlling the spread of COVID-19 and protecting national security. As in consecutive years past, government authorities took harsh reprisal measures against human rights defenders in China, Hong Kong, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and areas populated by Tibetans.

Nonetheless, human rights defenders demonstrated remarkable resilience and tremendous courage. Even while facing the increasingly draconian rule of President Xi Jinping, they persevered in pressing for protecting and promoting human rights. They strived to advocate for labor rights, women’s rights, housing and land rights, freedom from torture and freedom from discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and disability.

In this report, we identify several measures imposed against human rights defenders in 2021 that were notable for the harshness, speed, and systematic thoroughness of their implementation, including but not limited to:

- Criminal prosecution of citizen journalists and online campaigners who disseminated and gathered information about rights violations.

- New and tighter restrictions on the rights to free association, free expression, and peaceful assembly.

- Tightened control over human rights lawyers, including new rules that further constrict their freedom of expression, and targeting of lawyers who took on cases of human rights defenders, or who voiced support for rights defenders on social media.

- Continued impunity of police who subjected human rights defenders to torture and other forms of ill-treatment and retaliation against people who exposed such torture.

- The dismantling of democratic and rule of law institutions in Hong Kong, using the National Security Law to crack down on the press, independent civil society, opposition lawmakers, and those who sought to preserve memories of 1989 Tiananmen Massacre victims.

- Doubling down on repressive policies in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and areas populated by Tibetans while denying allegations of crimes against humanity. Many ethnic, cultural, and religious rights defenders, poets, entertainers, historians, and other intellectuals in these areas remained in detention, serving long prison terms. These regions remained effectively off-limits to the international community.

CHRD has documented more than two thousand cases of prisoners of conscience since 2019. During the year of 2021, 120 documented prisoners of conscience were taken away—meaning deprived of liberty by authorities—and 202 documented prisoners of conscience were sentenced to prison terms. All those documented faced punishment for peacefully exercising and/or defending freedom of expression, assembly, association, or religion, often while seeking equal protection and promotion of social economic cultural human rights. However, these figures represent only the cases CHRD and our partners were able to document and verify. Due to the family members of prisoners of conscience being unwilling to go public in some instances due to fear of retaliation and widespread media and social media censorship, these figures are potentially just the “tip of the iceberg.”

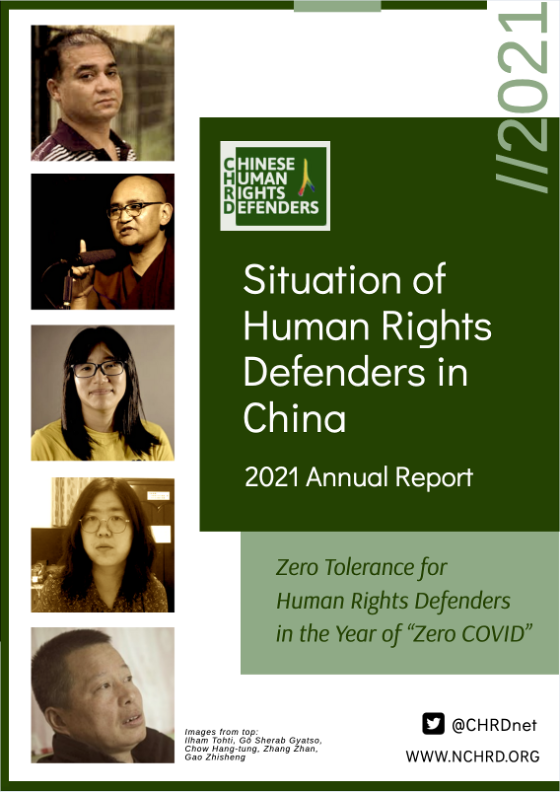

CHRD calls for the immediate and unconditional release of all detained and imprisoned human rights defenders and an end to reprisals against exercising and defending human rights. In each of the sections detailing the various thematic areas of punishment and retaliation below, CHRD identified priority cases that exemplify the patterns and trends observed throughout 2021, which we recommend as priorities for international campaigns and advocacy with PRC leaders:

- COVID-focused citizen reporters/critics: Zhang Zhan, Fang Bin, He Fangmei

- Hong Kong civil liberties defenders: Hang-tung Chow, Albert Ho, Lee Cheuk-yan.

- Social and economic rights defenders: Zhou Weilin, Li Yufeng, Chen Jianfang, Huang Xueqin, Wang Jianbing

- Defenders exercising freedom of assembly and association: Xu Zhiyong, Ding Jiaxi, Huang Qi, Qin Yongmin, Cheng Yuan, Wu Gejianxiong

- Defenders exercising free expression online: Ou Biaofeng, Wang Aizhong

- Human rights lawyers: Qin Yongpei, Li Yuhan, Gao Zhisheng

- Defenders seeking accountability for state torture: Li Qiaochu, Chang Weiping

- Defender of cultural rights and religious freedom in the XUAR: Gheyratjan Osman

- Defender of cultural rights and Buddhist scholar: Gō Sherab Gyatso

Depriving Liberty of COVID Reporters and Critics

During 2021, the Chinese government zealously pursued a “Zero-COVID-19” policy, aiming to suppress outbreaks of any size at any cost. This approach contributed to keeping COVID case rates at bay domestically, but it also justified the government’s unchecked use of surveillance technology and social controls and the curtailing of freedom of movement both within and out of the country, with the effect of practically shutting down the remaining space in which human rights defenders were operating. Many scholarly visits, conferences, sporting events, and other normal international interactions were cancelled or delayed. At the time of this report’s publication, even after the development of vaccines and other treatments, the Chinese government appeared to be extending its strict COVID-19 controls for at least 2022, with possible changes in 2023..

In 2021, government officials continued to hold in custody several citizen journalists and health rights activists who had been the first to report on or publicly question government measures in the crucial early days of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan in:

- Zhang Zhan, a citizen journalist, remained in prison with life-threatening health conditions. She was sentenced to four years in prison on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” for her reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic. In August 2021, Zhang Zhan’s mother revealed that Zhang Zhan’s weight had dropped to 40kg (88lbs) after maintaining a hunger strike to protest her innocence. She also suffered from malnutrition, ulcers, and fluid retention in her limbs. Although her health deteriorated continuously through 2021, authorities persisted in denying her medical parole.

- Fang Bin, a citizen journalist, remained incommunicado for most of 2021. He began reporting from Wuhan in early 2020 and posted videos about the COVID outbreak. He has been missing since being detained by police shortly afterward. In November, however, a report emerged indicating he might be in a detention center awaiting trial.

- Chen Qiushi, a lawyer and citizen journalist, reappeared to the world in October 2021. In early 2020, he posted videos to social media reporting on the outbreak from Wuhan, after which he went missing for nearly two years. After his release, he released a video in which he described being secretly detained without even his parents being informed of his whereabouts.

- He Fangmei, a health rights advocate, remained forcibly disappeared throughout 2021, and officials have not shared any information regarding her circumstances since her disappearance. She went missing after staging a protest in front of China’s National Health Commission in Beijing as China started to launch its COVID-19 vaccination drive in September 2021. She first became involved in health rights advocacy after her child was paralyzed following vaccination for hepatitis A, measles, and tetanus/diphtheria/ pertussis (TDAP), staged a protest in front of China’s National Health Commission in Beijing in September 2020, when China started to launch its COVID-19 vaccination drive. She subsequently went missing. Throughout 2021, she remained a victim of an enforced disappearance, with no news of her whatsoever.

HRDs throughout China reported that authorities used COVID prevention measures as a pretense to control or obstruct their activities. Lawyers and family members were often denied requests to visit people held in detention centers. Regular citizens found it nearly impossible to leave the country due to exit controls and the government putting a “pause” on issuing passports.

Retaliation against Defenders of Civil Political Liberties in Hong Kong

During 2021, Beijing continued to dismantle institutions maintaining democracy and rule-of-law in Hong Kong, using the National Security Law (NSL) to persecute human rights and democracy advocates and crush all sources of pro-democracy sentiment in the city.

Mass arrest of political opposition. On January 6, 2021, the Hong Kong government arrested 53 opposition lawmakers, including such notable figures as democracy activist Joshua Wong, professor Benny Tai, legislator Claudia Mo, and human rights lawyer John Clancey. They were charged with “subversion” under the NSL for having conducted political party primaries in 2020—a common practice for political parties globally to determine the leading candidates to put forward in a general election. The charge of subversion carries a maximum sentence of life in prison.

Mass arrests and prosecution of civil society leaders and protesters: HK national security police arrested editors from independent media outlets and forced them to cease operations. At least 50 civil society groups have shut down in the face of government threats to investigate and prosecute group members. To date, 175 civil society leaders and protesters have been arrested under the NSL, and many have been denied bail, including:

- Hang-tung Chow, a barrister who was the former vice chair of the Hong Kong Alliance, was sentenced to 15 months in prison for inciting an unauthorized assembly. The Hong Kong government did not allow the Hong Kong Alliance to hold its annual vigil in Victoria Park commemorating the victims of the 1989 massacre of pro-democracy protestors in and around Tiananmen Square. The government first claimed the vigil could not go forward due to COVID-19 restrictions, but later banned the event on political grounds and warned people that they risked five years of imprisonment if they attended. Given that people could not congregate at Victoria Park, where in the past crowds larger than 100,000 people had gathered every June 4th, Hang-tung Chow urged people to “light a candle wherever you are” and said she would be going to Victoria Park. She was arrested on June 4, but then released on bail the next day.

Shutting down civil society organizations: In an ostentatious act of reprisal, HK authorities crushed the Hong Kong Alliance. On September 9, 2021, the Hong Kong justice secretary charged the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, the group’s chair Lee Cheuk-yan, and the vice-chairs Chow Hang-tung and Albert Ho, with “inciting subversion.” Police had arrested Chow on September 8, while Lee and Ho have been jailed for their activism since April and May, respectively. Chow, and four other leading members of the group, Tang Ngok-kwan, Simon Leung, Chan To-wai, and Tsui Hon-kwong, were separately charged with “failing to comply with a notice to provide information.” All five were denied bail.

Their arrest stems from the Hong Kong Alliance’s decision not to cooperate with a police request made on August 25 to provide detailed information related to their interactions with or material support from several foreign groups and unspecified “foreign or Taiwan political parties and other groups with a political purpose, including at their Hong Kong branches” dating back to 2014. The police charged them under Article 43(5) of the National Security Law (NSL), alleging that the Hong Kong Alliance and its members were “foreign agents.” The move seemed to contradict the plain meaning of Article 39 of the National Security Law which says that the law can only be applied to acts committed after it came into effect on July 1, 2020.

Denial of international law protections: In a decision that could set an ominous precedent, in November, activist Ma Chun-man, known as “Captain America,” was sentenced to 5 years and 9 months in prison on the charge of inciting secession. His argument that his speech was protected by Basic Law, which makes reference to the protections under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), was rejected by the courts, signaling that judges will be unlikely to apply international human rights laws and standards to national security cases, which they had previously applied quite extensively.

Targeting Defenders of Social Economic Human Rights

Throughout 2021, the Chinese government continued its sustained persecution of defenders of social, economic, and cultural human rights through the deprivation of individuals’ civil and political rights and shutting down independent civil society organizations promoting equity and social justice. This trend, pronounced under Xi Jinping’s reign, has intensified during the COVID pandemic.

Mostly notably, among the persecuted defenders, are labor rights, land/housing rights, andwomen’s rights defenders:

- Chen Guojiang, a labor organizer and delivery worker, was detained on February 25 in Beijing. Chen, a popular social media activist, had frequently posted about the precarious working conditions of frontline delivery workers in Chinese cities and had recently called for delivery workers to boycott companies that allegedly withheld bonus pay for workers who could not meet high demand targets during the Chinese New Year holiday period. Chen was appalled at the working conditions in the sector, and he became one of the founders of a WeChat group dedicated to connecting, organizing, and providing rights defense and assistance to delivery workers. Chen frequently spoke out on Weibo about the precarious labor conditions of delivery workers and made videos, in an effort to garner support from the general public. Chen was subsequently detained on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” His father tried to raise funds for Chen’s legal fees, but he was pressured by the authorities to stop doing so. Details about Chen Guojiang’s subsequent arrest and trial were limited since his case was dealt with in a secretive manner. On 3 January 2022, Chen was seen in a video leaving prison. In an indication of the possible impact possibly of Chen’s activism, in June 2021 six government departments issued guidelines that gave delivery workers a guaranteed minimum income, insurance, and more flexibility on deadlines—addressing some of the concerns raised by delivery workers organized by Chen Guojiang.

- Zhou Weilin, a citizen journalist who regularly reported on labor issues and worked to protect disability rights, was sentenced to three and a half years on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Zhou was sentenced for his reporting and comments on Twitter. He was a victim of an occupational accident that left him disabled and had worked with Rights Defense Network (维权网).

- Li Yufeng, a grassroots rights defender, languished in prison in 2021 after she was sentenced to four years on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” She was held in pre-trial detention for nearly two years following her detention on August 8, 2019 after she accompanied a friend to Beijing to lodge grievances against local officials at the Supreme People’s Court. The case against her was based on three main points: accepting foreign media interviews after she was released from prison in which she disclosed her ill-treatment in prison, singing songs to mock her government minders while “being forced to travel” to a local tourist site by the police, and “insulting” and cursing her government minders on multiple occasions. Her sentence was also connected to her longstanding petitioning as a victim of a forced eviction and her solidarity with other housing rights activists.

- Chen Jianfang, a housing rights defender, was sentenced to three years on the charge of “inciting subversion of state power” in March. Authorities used fraudulent means to prevent Chen from gaining access to legal representation, ultimately denying her any access to a lawyer for over two years. On March 2, 2021 Chen met with a lawyer, but Chen challenged if the lawyer was indeed a real human rights lawyer and not an impostor and she requested lawyer Wang Yu, who she knew, to verify the lawyer’s identity. On the day of the trial, police blocked Wang Yu from leaving her hotel room. Chen was apparently put on trial without being represented by a lawyer of her own choosing.

- Wang Jianbing and Huang Xueqin were taken away by authorities on September 19 2021in Guangzhou. Wang was an activist who worked to help workers suffering from the lung disease pneumoconiosis and other occupational illnesses. Huang was a journalist and feminist who was one of the leaders of China’s #MeToo movement. The authorities, in violation of China’s Criminal Procedure Law, did not send the family of Wang or Huang detention notices. In addition, the Haizhu District Police Petitioning Office Chief said Wang Jianbing’s case was being handled by the Guangzhou Police, but he said he could not reveal the specific crime or the criminal coercive measures taken. Finally, an arrest notice dated October 27 was sent to Wang’s family saying he was arrested on the charge of “inciting subversion of state authority” and that he was being held at the Guangzhou No. 1 Detention Center. But friends and family have reported that they have been unable to find his name and ID number in the detention center’s online system for depositing funds for detainees’ to use at the prison commissary. Lawyers have been unable to visit him, raising doubts as to whether he is being held there.

It is unclear to what extent Huang Xueqin’s detention is an act of retaliation for her #MeToo activism. But the risks of coming forward with sexual assault allegations against powerful men became clear to the world on November 2 when tennis star Peng Shuai posted on social media that a high-level official had sexually assaulted her. Her post was scrubbed from the Chinese web within minutes, and she appears to have been under the control of authorities since then.

In the spring of 2021, at least 20 accounts belonging to prominent and influential feminists were banned by Weibo and other social media platforms. The banning typically occurred after they were harassed online and often accused of treason or supporting Hong Kong independence or Uyghurs, which are very sensitive topics in the Chinese context. This harassment was often led by state-affiliated nationalist accounts.

Persecuting Defenders Exercising Freedom of Assembly & Association

In 2021, HRDs who exercised their freedom of association to organize advocacy efforts were detained, imprisoned, silenced, or forced into exile. No independent human rights advocacy organization operated openly on mainland China.

In March 2021, 22 ministries and departments jointly issued a new Notice on Removing the Breeding Ground for Illegal Social Organizations and Cleansing the Ecological Space of Social Organizations, which sought to deny independent social organizations any legal status, political capital, funding or assistance, media and internet coverage, or any venue for carrying out activities.

This all-encompassing approach to suffocating any exercise of the right to freedom of association was exemplified in the persecution of Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi – two tenacious advocates for new ideas for the development of civil society and public participation. Xu Zhiyong,a legal scholarand Ding Jiaxi a lawyer and activist, were indicted in January 2021 on the charge of “inciting supervision of state authority” and are awaiting trial. Both have long histories of helping disadvantaged populations protect their economic, social, cultural, and civil political rights, and are leading figures in the “New Citizens Movement.” Their indictments showed how the government sought to control private gatherings among friends and to limit discussion and the sharing of ideas online, including about social movements.

In August 2021, Ding Jiaxi and Xu Zhiyong were indicted, and the prosecution’s case against Ding Jiaxi and Xu Zhiyong demonstrated how the government has tried to criminalize freedom of speech and freedom of association by claiming that informal discussions and gatherings amount to “illegal social organizations.” Specifically, the points raised by the prosecution were related to Ding’s involvement with the “New Citizens Movement,” which had attempted to popularize a new form of civic engagement. The indictment also accused Ding of organizing the “Citizens Movement,” creating a Telegram channel and convening the Xiamen meeting. It also cited various articles written by Ding, including one in which he urged Chinese citizens to stand for elections. Two of the “witnesses” against Ding and Xu, Wang Jiangsong and Dai Zhenya, publicly stated that the government mischaracterized their testimony. Ding Jiaxi also filed complaints to have the “illegally obtained evidence,” meaning confessions extracted through torture, dismissed from court proceedings.

Xu Zhiyong’s strategy of promoting a “New Citizens’ Movement” emerged in the early 2010s. It was focused on promoting the implementation of civil and human rights embedded in China’s constitution, Chinese laws, and regulations. His now banned organization encouraged citizens to take actions on a local level, often on issues that affected regular people such as equal educational opportunities for migrant laborers’ children.

By arguing that the “New Citizens Movement” and “Citizens Movement” were “illegal organizations,” despite there being no tangible organization in existence, the government has tried to discredit and criminalize the whole social movement and the ideas associated with it.

Another manifestation of harsh clamping down on exercising freedom of association in 2021 was the government’s ban on LGBT student groups on university campuses. In May and June, LGBT student groups in Hubei, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Tianjin, Hunan and other locations were questioned by university administrators. The Education Department of Jiangsu Province put out a regulation on handling student groups, requiring universities “thoroughly inspect” them for “feminist, gay, or “sexual minority” groups,” and “in a timely manner, rectify [i.e, close] any [social media] accounts involving the university that have not received official approval.” On July 6, 2021, nearly 20 accounts of university LGBT and gender studies were suddenly shut down on WeChat. These accounts were affiliated with LGBT groups at some of China’s most prestigious universities, such as Peking University and Fudan University. There was no clear explanation given to the groups, and there was no immediate triggering incident to explain the logic or the suddenness of the ban.

In 2021, several criminally prosecuted leadership figures of independent civil society organizations that once advocated for human rights remained in prison:

- Liu Feiyue, who had run the website Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch, served out his 5-year prison sentence. He was released upon completing a five-year term on 17 November 2021. Several affiliates of his group remain in prison.

- Huang Qi, a citizen journalist who created a website 64 Tianwang dedicated to publicizing human rights abuses, remained in prison and his mother, who is dying of lung cancer, was not permitted to visit him throughout 2021. He founded a website, 64 Tianwang, which was dedicated to publicizing human rights abuses. In 2019, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison on the charge of intentionally leaking state secrets” and “illegally providing state secrets to foreign entities.”

- Qin Yongmin, founder and leader of the Chinese Human Rights Watch (known as the “Rose Group”) remained in prison, now serving the eighth year of a 13-year sentence for “subversion of state power.” Qin suffers from poor health with high blood pressure and a lung condition without proper care in prison.

- Cheng Yuan, Liu Yongze and Wu Gejianxiong, staff members of the NGO Changsha Funeng, were sentenced in a secret trial to five years, two years and three years imprisonment, respectively, although the international community only learned about the news in August. Their family members were not informed about the trial and state-appointed lawyer refused to provide Cheng Yuan’s wife with the verdict. Changsha Funeng sought to prevent discrimination and strengthen protections for individuals living with disabilities and with HIV/AIDS and other communicable diseases. In 2020, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found their detentions to be arbitrary and called for their immediate release, but Chinese authorities did not comply.

Throughout the year, the government went after business tycoons who were accused of providing financial support to independent organizations, such as Sun Dawu. Sun, an agricultural entrepreneur and philanthropist, had a strong commitment to social justice issues in China. In July, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison. In addition, 19 other defendants, including his adult children and numerous employees, were also sentenced and his company was fined nearly 130 million USD.

Criminalizing Defenders Exercising Free Expression Online

The Chinese government continued to run the world’s largest censorship apparatus and to aggressively track and intimidate critics outside China’s borders. In recent years, the government has tightened its control over the traditional media and launched crackdowns on independent social media platforms, especially those focused on documenting human rights cases and news, such as 64 Tianwang and Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch (mentioned above). Due to these restrictions, individual activists on social media have played an ever more important role in gathering and disseminating information and news. As the space for on-the-ground civil society activities have all but closed by 2021, online social media platforms have remained the forefront for human rights activism. As a result, they have become the target of heavy cyber policing, high-tech surveillance, and state censorship.

Two defenders persecuted by the Chinese government for exercising their freedom of expression online stood out in 2021:

- Ou Biaofeng, an activist who has been vocal in supporting many other activists and causes on social media, was taken away by police on December 2, 2020 and subsequently placed in administrative detention for 15 days on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” However, as his 15 days in administrative detention came to an end on December 18, 2020, Ou Biaofeng was placed under “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) on the charge of “inciting subversion of state power.” He was arrested on the same charge on July 22, 2021 and transferred to the No. 1 Zhuzhou Municipal Detention Center.

The incident that led to Ou Biaofeng’s detention was his tweeting on behalf of Dong Yaoqiong, a woman who was detained in July 2018 and forced into a psychiatric facility after she threw ink at a picture of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Dong was ostensibly released in January 2020, but at the end of the year, Dong released an emotional video describing how constant state surveillance since her release had driven her to the verge of a breakdown. Ou Biaofeng tweeted about her case, and helped her to tweet out a message to the world, since she presumably could not tweet due to state pressure.

Over the last decade, Ou Biaofeng supported many causes and spoke out for many human rights defenders. He often provided details and updates for particular cases on social media. He spoke out for the human rights lawyers and their associates who were victims of the notorious “709” crackdown. In 2014, Ou Biaofeng voiced his support for the Hong Kong democracy movement online.

- Wang Aizhong, a social media activist who highlighted vulnerable communities, was taken away by police from his home in Guangzhou on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” on May 29. Police also confiscated 29 books, two computers, and one cell phone. It was notable that the raid took place just days before the June 4th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre. It was especially alarming as he had been detained in 2014 as part of a nationwide sweep of dissidents leading up to the 25th Tiananmen anniversary. On July 6, police formally arrested Wang. He is held at Guangzhou Tianhe Detention Center.

Sources indicate that his wife has been repeatedly questioned by the police about Wang Aizhong’s activities, and concerns about his social media posts have dominated the interrogations. The police told her that Wang was being detained because of his posts and for giving foreign media interviews. The police also threatened to end her job as a flight attendant if she continues to speak out about Wang’s case. She has refused to keep silent. While in detention, Wang has lost 10kg due to poor nutrition and he has been prevented from purchasing extra food or toiletries from the commissary.

Squeezing Human Rights Lawyers

In 2021, lawyers in China continued to come up against tremendous obstacles and punishments when they attempted to use Chinese law to defend the legal rights of their clients in cases deemed “politically sensitive” by authorities. Although Chinese law ostensibly guarantees all suspects in criminal cases to the right to legal counsel, in reality, Chinese authorities block access to justice for those prosecuted for dissent or challenging government policy or official abuses by revoking their lawyers’ licenses; threatening, harassing and detaining lawyers; denying detainees access to lawyers of their choice; forcing detainees to dismiss their lawyers; and restricting lawyers’ access to case files. International standards state that, “lawyers shall not be identified with their clients or their clients’ causes,” but the Chinese government routinely penalizes lawyers for trying to defend clients detained for human rights activism or expressing dissent.

On October 15, 2021, the All-China Lawyers Association issued alarming new rules, All-China Lawyers Association On Prohibiting the Hyping of Cases in Violation of Rules, that authorize authorities to restrict the free expression of lawyers and make it nearly impossible for lawyers to expose due process violations by police or court officials.

Throughout 2021, several lawyers faced government retaliation for trying to carry out their professional work:

- Lin Qilei,a lawyer, was informed on October 31, 2021 by the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Justice that his law license had been revoked. Lin had represented one of the “Hong Kong 12” last year—activists who were intercepted at sea by China’s Coast Guard while trying to escape from Hong Kong and who were subsequently detained in mainland China. Lin had also previously defended human rights activists like Guo Feixiong, democracy activists like Qin Yongmin, and Tibetans allegedly unfairly targeted by the government.

- Liang Xiaojun, a lawyer, had his law license revoked on December 16, 2021 by the Beijing Justice Department. The decision cited Liang Xiaojun’s use of domestic and foreign social media platforms, open support of Falun Gong, referring to Marxism as “poison,” and insulting and smearing the General Principles of the Chinese Constitution.

However, in an interview, Liang cast doubt on this official explanation. He had been supporting Falun Gong practitioners for well over ten years, making the timing of his license revocation hard to justify. A disbarred lawyer Wu Shaoping speculated that the real reason for Liang’s disbarment could be for Liang’s defense of his client Xu Zhiyong. Moreover, Liang Xiaojun had also represented one of the “Hong Kong 12.”

Lu Siwei and Ren Quanniu, two other lawyers who undertook legal representation to defend two of the “Hong Kong 12, also had their licenses revoked in early 2021.

Meanwhile, in 2021, several human rights lawyers remained in detention or forced disappearance:

- Qin Yongpei, a disbarred human rights lawyer from Guangxi, was detained in October 2019, in apparent retaliation for criticizing on social media the corruption of high-level Chinese officials, remained in detention throughout 2021. On December 31, amidst a heavy state security presence, Qin went on trial at the Nanning City Intermediate Court in a hearing that was not open to the general public. His lawyer wanted seven witnesses to attend, but the court did not allow the defense’s witnesses to testify. The sentence will be announced at a later date.

- Li Yuhan, who had defended fellow lawyer Wang Yu in the 2015 crackdown and who has languished with poor health in pre-trial detention since October 2017, finally went on trial at the Heping District People’s Court in Liaoning on October 20, 2021. Diplomats from six countries tried to attend, but they were denied entry on the pretext that there were “no available seats.” Her lawyers Xie Yang and Wang Yu were also not allowed in the courtroom. The trial ended without a verdict. The judge is to pick another date to announce the sentence.

- Gao Zhisheng, the disbarred and previously jailed human rights lawyer who disappeared in August 2017, remained in state enforced disappearance with his whereabouts unknown through the year. Having heard nothing about him in four years, his wife, Geng He, sent a message to the Chinese government on April 20, Gao Zhisheng’s birthday: “If he’s alive, let me see his face; If he’s dead, let me see his corpse.” But the government did not respond.

- Jiang Tianyong, a former human rights lawyer who got out of prison on February 28, 2019 having served two years on the charge of “inciting subversion of state power”, remained under house arrest conditions throughout 2021. Since his release, Jiang’s home has been surrounded by at least eight plainclothes guards stationed in sheds near his house who monitor his every movement in person and through surveillance cameras. In May, Xing Wangli, a human rights defender, was detained after having visited Jiang Tianyong to show solidarity with him.

Rights Defenders Holding Torturers Accountable

Torture continued to be Chinese security police’s routine method of punishment or treatment of detained human rights defenders and political dissidents in 2021. What is worse, as a pattern that has emerged clearly in the last few years, is that when torture victims and counter-torture activists disclosed details of torture or sought accountability from law enforcement for committing the acts of torture, which the Chinese law claims to “forbid,” they faced harsh retaliation by the police—who sometimes subjecting them to torture.

This trend of torturing counter-torture activists and outspoken victims of torture is all the more alarming given that the Chinese government, a party to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) since 1988, is obligated under the treaty to conduct “…a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed”.

A case in point is that involvingNiu Tengyu, an IT manager for a website called Esu.Wiki. Niu was subjected to torture during his secret detention by police before he was sentenced to 14 years after the website he managed revealed private information related to Xi Jinping’s family and other high-ranking officials.

While Niu was held in the notorious secret detention system known as “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) in late 2019 and January of 2020, every two or three days, he was stripped naked, his naked body photographed, and hung up by his wrists. Police officers would whip and beat and berate him. Police interrogators burnt his private parts with a lighter and would also pour saline solution on his private parts. The officers tried to force Niu to confess by inflicting the pain and humiliation. Each of these torture sessions would typically last approximately two hours.

After Niu’s mother learnt about these horrific details of torture of her teenage son, she exposed them and sought to hold the police accountable. She faced threats and her online posts were promptly censored. Niu’s lawyers’ request to dismiss illegally obtained coerced confessions was granted.

- Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi. It also emerged that the two activists, mentioned above, had been tortured while they were in China’s notorious secret detention system known as “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL). While being interrogated in Yantai, Shandong, Xu Zhiyong was tied to an iron interrogation chair for 10-plus hours per day. Authorities tied his arms and legs to the chair, making it difficult for him to breathe. Each meal consisted of one mantou (a bland Chinese bun), and he was taken to the interrogation chambers in a black hood. Similarly, in his first interrogation sessions, Ding Jiaxi was given extremely limited quantities of food and water: one quarter of a mantou and 600ml of water, with no other food. From April 1-8, Ding was fastened to a “tiger chair,” with his back tightly tied to the chair, and with a band tightly tied around his chest, which inhibited regular breathing. Every day he was interrogated from 9am to 6am the next morning. From 6am to 9am, he was allowed to use the bathroom and eat, but he was not allowed to sleep. Officials utilized these torture methods 24 hours a day. By the morning of April 7, they found that due to sitting in the tiger chair for too long, his feet had swollen up into round balls and he was physically depleted.

Ding Jiaxi and his wife have both filed applications to exclude “illegally obtained evidence”—meaning confessions obtained through torture—although as of publishing these applications appear to have been unsuccessful.

The government has not investigated many such claims of torture by victims and their families or lawyers and officials have retaliated against those who publicized torture allegations and sought police accountability for committing acts of torture. Several human rights defenders and rights lawyers who spoke out about torture and urged criminal investigation of accused police officers have suffered further retaliation, including being subjected to torture themselves:

- Li Qiaochu, the labor rights and #MeToo activist, made public many details of torture that the legal scholar and activist Xu Zhiyong (her partner) and lawyer Ding Jiaxi had been subjected to. On February 2, 2021, Li filed complaints against the Linshu detention center for not providing food in accordance with national regulations and she filed a complaint against the Linyu Public Security Bureau for its alleged ill-treatment of Xu by withholding food. On February 6, she was taken away from her Beijing home by police from the same division allegedly responsible for the torture against Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi that she had publicized. It was a clear act of retaliation against her efforts to against torture. She was eventually charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and was repeatedly denied access to her lawyers until August, when she saw a lawyer for the first time. She was denied medical parole on ten occasions, despite suffering from hallucinations and medical conditions while in detention.

- Chang Weiping, a human rights lawyer, posted a video in October 2020 on YouTube about his own experiences of being tortured by police when he had been detained in January 2020. In the video, Chang described being forced to sit on a “tiger chair,” a torture device used to constrict and cause pain during interrogations, non-stop for ten days, with the exception of bathroom breaks. A few days after he posted the video, authorities took him away and forcibly disappeared him for six months under the RSDL system. He was formally arrested for “subversion of state power” on April 7, 2021. From October 2020 until September 14, 2021, nearly one year, Chang was denied access to a lawyer. When he finally gained access to his lawyer in September 2021, he told the lawyer about being tortured in retaliation for exposing his torture by police during his previous detention. He was once tied to the “tiger chair,” once without break for six days and six nights. Police subjected him to sleep deprivation and coerced him into repeating the police’s talking points during interrogation, refusing to allow him to sleep unless he complied. He was also deprived of nutrition on daily basis—he was provided with a meager ration of food that was of very poor quality. The police also subjected him to psychological torment.

Targeting Defenders of Cultural Rights and Religious Freedom in Xinjiang and Tibet

Throughout the year of 2021, evidence continued to mount that the Chinese government had engaged in crimes against humanity in Xinjiang. Survivors of mass detention of an estimated one million in re-education camps have reported systematic rape, torture, and deaths.

In both the Xinjiang and Tibetan regions, populated by “ethnic minorities,” the Chinese government militarized security measures—invasive policing and community surveillance, including through “big data analytics,” and destruction and control of mosques and monasteries—of recent years have practically eliminated any independent voices and expression of Uyghur, Tibetan, and other ethnic, cultural, and religious identities.

According to Chinese authorities, including in leaked speeches by top leader Xi Jinping that came to light in 2021, unprecedented mass internment camps and other coercive social policies in Xinjiang were needed to fundamentally change the culture of ethnic minorities and impose “correct view of the motherland and nation,” which would lead to fewer “separatist” and “religious extremist” thoughts.

In this context of repression, those who have tried to preserve or transmit their ethnic cultural and religious heritage—intellectuals, academics, writers, poets, historians—have been targeted by the government in its campaign to eradicate or alter their identities.

While some camp detainees may have been released, many others, including prominent cultural figures, remain detained in 2021:

- Gheyratjan Osman, a respected professor of Uyghur language and literature at Xinjiang University, was taken away in 2018 and sentenced to 10 years for “separatism,” although the legal details of his case remain unclear. The details of his case only emerged in August, when Radio Free Asia confirmed the basics of his case with three employees at Xinjiang University. However, information was limited as these individuals said they could not divulge more as the case was classified a “state secret”.

Gheyratjan Osman was apparently jailed on the grounds that he “rejected national culture,” attended a seminar on Turkic studies in Turkey in 2008 and gave “excessive” praise of Uyghur culture in his writings, which “inculcated separatist ideology in generations of Uyghur students,” according to the Chinese government as reported by RFA.

Gheyratjan Osman has published more than 30 books and 200 scholarly articles on the Uyghur language, literature, and folklore, including research on ancient Uyghur literature, The History of Classical Uyghur Literature, and Uyghurs in the East and the West.

- Qeyum Muhammad, an actor and associate professor at the Xinjiang Arts Institute, was found to have been taken away three years ago according to staff from the Xinjiang Arts Institute. The staff did not know the reason or where he was held. According to Radio Free Asia, Qeyum Muhammad had taught young Uyghur performers and comedians, and thus contributed to passing on Uyghur culture to younger generations.

- Ilham Tohti, a professor at the Central University for Nationalities (Minzu University) in Beijing and a leading advocate of Uyghur issues who co-founded the website Uyghur Online, remained in detention for life on the charge of “splittism”. His family was unable to visit him or to learn anything about his status throughout the year.

- Gō Sherab Gyatso, an eminent Tibetan Buddhist scholar and educator, was sentenced to 10 years on the charge of “inciting separatism,” the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD) learned in 2021. He was originally detained in October 2020 and was a victim of enforced disappearance for five months.

- Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan language advocate, was released from prison in January after serving five years for “inciting separatism.” Tashi Wangchuk was detained by the government after he starred in a short documentary by The New York Times following him as he attempted to use Chinese legal channels to file a lawsuit and a petition about China’s language policies. After his release, Tashi Wangchuk continued to speak out about the efforts of Chinese leaders to eradicate use of the Tibetan language. He showed that many prominent Tibetan websites had been banned. On January 17, 2022, Tashi Wangchuk was summoned by the police after he tried to meet with Yushu officials to discuss increasing the role of Tibetan in local school curriculum.

During the year, many Tibetan writers and intellectuals continued to suffer persecution.

Recommendations

CHRD takes this opportunity to urge the Chinese government to:

- End the arbitrary detention of anyone who exercises and promotes human rights;

- Revise legislation on counterterrorism, state secrets, and criminal statutes related to “subversion” and “inciting subversion” against state power to bring them in line with international human rights standards;

- Abolish the use of torture and enforced disappearances in all forms, and revise the Criminal Procedure Law to end the practice of “residential surveillance at a designated location”;

- In accordance with obligations under the CAT, conduct a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed; end reprisals against those seeking to end torture and end impunity for perpetrators of torture;

- Respect the rights to freedom of expression and press, end censorship, and dismantle the digital surveillance police state, including the Great Firewall;

- Respect the right of freedom of association, and revise laws that place onerous and unnecessary restrictions on civil society organizations;

- Respect the cultural rights of Uyghurs, Tibetans, and other ethnic minorities, and protect religious freedom;

- Release all peaceful protesters, journalists, and elected legislators in Hong Kong; repeal the un-democratically imposed National Security Law that violates the ICCPR, which applies to Hong Kong.

CHRD asks human rights-respecting governments to

- Make human rights a priority in policies across the board toward China and a priority in high-level discussions with Chinese leaders;

- Hold the Chinese government accountable and implement serious consequences for failures to respect human rights.

- Strengthen the UN international human rights system, play active roles in international human rights bodies and processes, and guard against China’s aggression to weaken key international human rights norms and institutions;

- Ask UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to immediately publish her office’s report on human rights violations in Xinjiang and support her demand for an unobstructed and independent visit to the region with guarantees from the Chinese government not subject those speaking frankly to her to reprisals;

- Initiate an immediate moratorium on the sale, transfer and use of surveillance technology until human rights-compliant regulatory frameworks are in place, limit the sale of technologies of mass surveillance to China;

- And provide strong and steadfast support to human rights defenders and civil society activists across China.

- Ensure that no human rights defender seeking asylum is returned to China, and provide for across-the-board, expeditated legal status to Uyghurs and other persecuted groups.